Kenya has officially eliminated sleeping sickness—human African trypanosomiasis (HAT)—as a public health problem, as validated by the World Health Organization (WHO). This landmark announcement elevates Kenya to the ranks of only ten countries to achieve this status and marks its second victory over a neglected tropical disease (NTD), following the successful eradication of guinea worm disease in 2018.

A Hard-Fought Battle Against a Deadly Threat

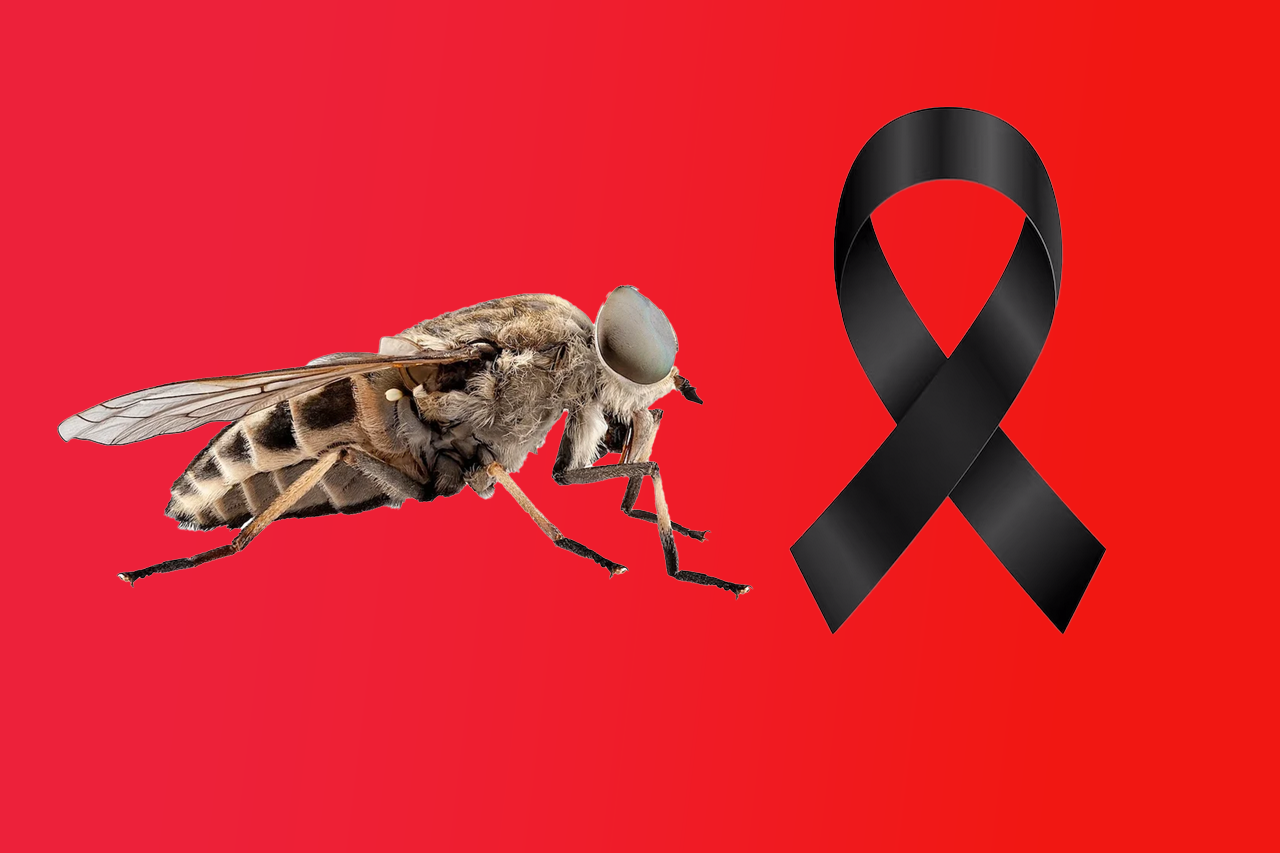

Sleeping sickness is a vector-borne disease caused by the parasite Trypanosoma brucei, transmitted through bites from infected tsetse flies. Kenya contends exclusively with the rhodesiense strain (r‑HAT), which is notably aggressive—capable of infiltrating the brain and systemic organs and typically fatal within weeks if untreated.

According to the (World Health Organization) the disease was first detected in Kenya in the early 20th century. Since then, sustained public health efforts have paid off—no indigenous cases have been reported since 2009, and the last imported cases trace back to 2012 from the Masai Mara Reserve.

Why This Achievement Matters

Protecting Vulnerable Communities

Rural populations—those dependent on agriculture, fishing, animal husbandry, or hunting—have borne the brunt of r‑HAT. By eliminating it as a public health concern, Kenya has safeguarded these communities from a disease that once carried immense morbidity and mortality.

A Landmark for NTD Control in Africa

The elimination underscores the effectiveness of collaborative efforts and solidifies Kenya’s role in the emerging narrative of Africa’s success in combating NTDs. “This is another step toward making Africa free of neglected tropical diseases,” proclaimed WHO Director-General Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus.

What It Took: Strategy, Partnerships, and Persistence

Kenya’s success stems from years of coordinated action:

-

Strengthening Disease Surveillance

Twelve health facilities across six historically endemic counties—Busia, Siaya, Kisumu, Homa Bay, Migori, and Kwale—were designated as sentinel sites. These were equipped with advanced diagnostic tools and staffed by healthcare workers trained specifically in r‑HAT detection(finddx,2024) -

Vector and Animal Disease Control

Surveillance and control of tsetse flies and animal trypanosomiasis were ramped up in collaboration with Kenya’s veterinary authorities and the Kenya Tsetse and Trypanosomiasis Eradication Council (KENTTEC), effectively disrupting disease transmission chains (World Health Organization,2025). -

Valuable Global Support

International partners played pivotal roles. FIND (Foundation for Innovative New Diagnostics) partnered with Kenya’s Ministry of Health since 2020 to map health facilities, enhance labs, train clinicians, and boost community awareness (finddx, 2025). -

Multisectoral Collaboration

Kenya’s Ministry of Health, counties, research institutions, WHO, and private collaborators rallied behind this goal, ensuring streamlined action and resource allocation (World Health Organization,2025)

The Road Ahead

Post-Elimination Vigilance

Eliminating r‑HAT as a public health problem doesn’t negate the risk of resurgence. Kenya has committed to implementing a post-validation surveillance plan under WHO guidance. Continued monitoring in formerly endemic areas, along with maintaining stocks of essential treatments—courtesy of pharmaceutical partners like Bayer and Sanofi—are key elements of this strategy

Kenya’s Role in Africa’s NTD Landscape

Kenya now joins nine other African nations—Benin, Chad, Côte d’Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Ghana, Guinea, Rwanda, Togo, and Uganda—in having eliminated HAT as a public health threat(World Health Organization,2020)

Globally, a total of 57 countries have eliminated at least one NTD, advancing the WHO’s 2030 Roadmap. Kenya’s achievement deepens that momentum—but as international health financing tightens, sustained investment remains critical.

Celebrating a Win, Maintaining the Guard

This success affirms that even among marginalized populations, robust health systems and focused interventions can break the cycle of chronic disease burden. For Kenya, this achievement isn’t just a milestone—it’s a testament to perseverance and shared purpose.

Yet, health officials and observers caution that complacency risks undoing hard-fought gains. Continued funding, efficient surveillance, and community involvement are essential to keeping sleeping sickness at bay.

In summary, Kenya’s WHO validation marks a victory not just against sleeping sickness—but as a beacon of what determined, collaborative public health action can accomplish. Here’s to protecting vulnerable communities, reinforcing health infrastructure, and marching toward broader NTD elimination across Africa.